From One Culture to Another

By Michael Althshuler, JD, MS

The moving and nuanced aspects of effective communication are challenging. This is true when we are focused, thoughtful and well prepared. The presence of conflict, tension or lack of clarity geometrically increases the difficulties posed to well considered communication.

Conflict management is a structured task focused process. Value placed on the relationships of the involved parties can be as important as achieving a solution. In order to reach win-win solutions and attend to valued relationships, communication is central.

Communication is the exchange of information. You and I are sitting at the negotiation table. In my mind I have a thought or an idea that I would like you to understand. I will use words and phrases that I believe will express this thought or idea to you.

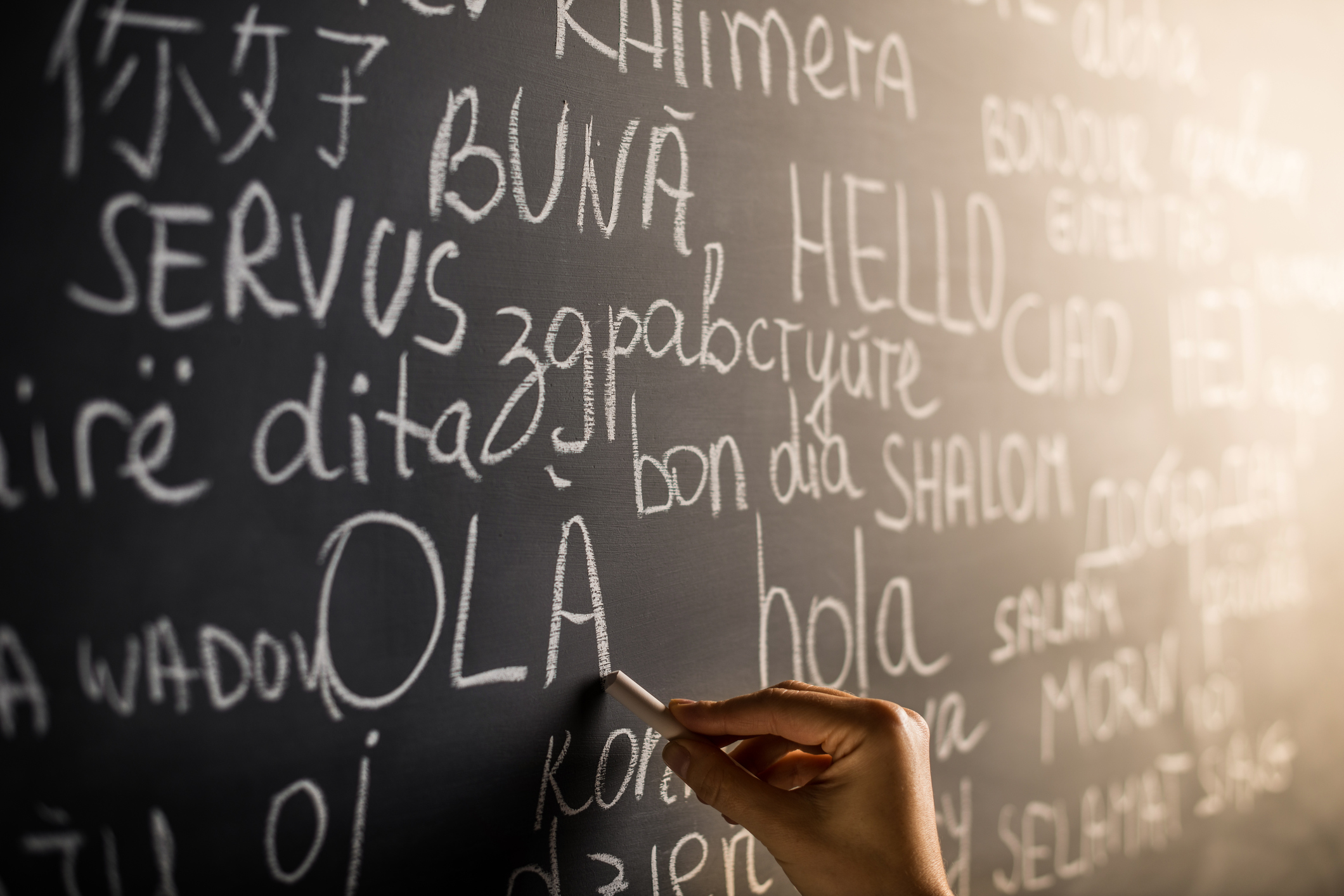

If we share the same language and cultural background, I will assume that words and phrases that have one meaning to me will have the same meaning for you. In the best- case scenario this can be a reasonable assumption. In the worst-case scenario, assuming that we each attach the same meaning to the same words and phrases can be a damaging mistake.

The process through which we learn to give meaning to language is lengthy and complex. Our age, family background, level and type of education, economic, social and political history are a few of the elements that comprise our ‘cultural’ background. Each single element can contribute a different shade of meaning to the words we use.

I am a native English speaking American. I now know that my ‘cultural’ frame of reference, the personal background that gives meaning to the language I use, may be significantly different from the frame of reference of many other native English-speaking Americans. I am a white, male, third-generation, Jewish, west coast urban, middle class, college educated, politically progressive.....and the list might go on.

When I work with others with whom I might share several of these background characteristics, I am mindful that there is a minefield of other cultural characteristics that we might not share in common, characteristics that mind result in our giving different ‘meaning’ to the same word.

When I am with others who are from a different country, or with whom I am speaking Spanish, or people whose first language is not English, I have learned to be very cautious about possible misunderstandings. One thing is certain, once a misunderstanding occurs, the likelihood for future misunderstanding is greatly increased.

Then there is the issue of body language, or non-verbal communication. For most of us, non-verbal behavior is mostly unconscious communication. Yet language experts claim that 67 – 90% of interpersonal communications are non-verbal. The meaning we give to body language, similar to the meaning we learn to give the words that we use, is altogether culturally determined.

One example of body language is eye contact. In most of the United States people expect that people who are honest and respectful will offer direct eye contact during a conversation. Yet there are many more traditional cultures around the world, and in the United States, where the individuals to whom you will offer direct eye contact is carefully limited by social indicators. In many native-American and Asian cultures, to offer direct eye contact to an elder would be considered confrontational and disrespectful, and would add an adversarial element to an attempted exchange.

How do we best navigate this minefield of possible miscommunication? Once we acknowledge that the meaning of language and non-verbal behavior is largely determined by culture, how can we adjust for these potential differences?

The ability to manage a productive problems solving climate where effective problem solving can occur requires a set of skills, a set of skill that can be acquired. Developing skills and learning to use them to advantage requires self-awareness and practice. Conflict, tension or lack of clarity make it difficult to objectively monitor the effects our own behavior and to use newly acquired skills. Focus and continued practice are essential.

Yet, misunderstanding can be avoided by being aware of the following:

- Be cautious before you assume that you have been understood. Although we may feel we have been clear in our communications, we are often surprised to learn what understanding others have taken from what we have said, or how the perceive us to have behaved.

- Be cautious before you assume that you have understood what others may be communicating, particularly when tension, significant language or cultural differences are present.